Sources of Gnosticism

There were only a few groups whose members expressly called themselves Gnostics (i.e. “the Knowing ones”), but this was after Bishop Irenaeus, who wrote against the Gnostics, had already used that term. Some of the early Fathers of the Church considered Gnosticism to be a Christian heresy. Their reports and refutations were confined to:

1) Systems that had sprouted from Christianity (such as the Valentinian system);

2) Systems that had adapted Christ to their pre-existing heterogeneous teaching (such as the Phrygian Naassenes); and

3) Systems that had a common Jewish background and were close enough to be felt as competing with or distorting the Church’s message (such as the school of Simon Magus).

Modern research has broadened the traditional range of what is considered “gnostic” by bringing light to the existence of pre-Christian Jewish Gnosticism, Hellenistic Gnosticism, and Mandaean sources (the Mandaeans are the most striking example of Eastern Gnosticism outside Hellenism).

Primary Sources

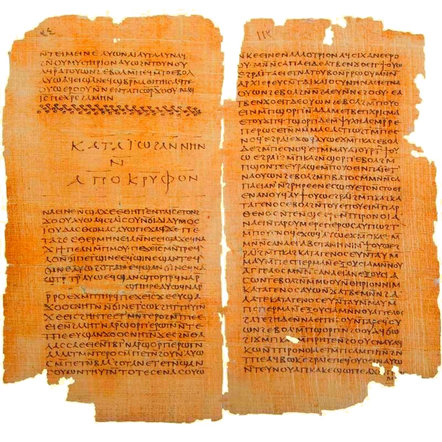

The primary sources of Gnosticism are Greek, Coptic, Aramaic, Persian, Turkish and Chinese. There are also the sacred books of the Mandaeans, a sect which survives in modern Iraq, and includes John the Baptist among its prophets. This is the only instance of the continued existence of a gnostic religion to the present day. “Manda” means knowledge, so Mandaeans means “Gnostics”. There are also Coptic-gnostic writings, mostly Valentinian. Coptic is the Egyptian vernacular language of the later Hellenistic period, descended from ancient Egyptian with a mixture of Greek. The promotion of Coptic as a popular language reflects the rise of a mass religion. In 1945 the miraculous Nag-Hammadi discovery in upper Egypt brought the Gospel of Truth of the Valentinians. Until then the Coptic-gnostic writings like the Pistis Sophia represented a declining stage of gnostic thought. Other primary gnostic sources are Manichaean Turfan fragments in Persian and Turkish; the Corpus Hermeticum first published in the 16th century (it was called Hermetic because of the syncretistic identification of the Egyptian god Thoth with the Greek god Hermes); Alchemicistic literature; Greek and Coptic magical papyri; and New Testament apocrypha.

Secondary Sources

Secondary sources about Gnostic thought are the anti-gnostic works of the Fathers Irenaeus, Hippolytus, Origen, and Epiphanius in Greek, Tertullian in Latin. Clement of Alexandria left writings of Theodotus, a member of the Valentinian school of Gnosticism. There are also refutations of Manichaeism. The mystery-religions of late antiquity (Mysteries of Isis, Mithras, and Attis) are gnostic insofar as they allegorized their ritual and their original cult-myths in a spirit similar to the gnostic one. Some Rabbinical literature and Islamic literature are also sources.

Adapted from: Jonas, H. (1963). The gnostic religion: The message of the alien God and the beginnings of Christianity. Boston: Beacon Press.

1) Systems that had sprouted from Christianity (such as the Valentinian system);

2) Systems that had adapted Christ to their pre-existing heterogeneous teaching (such as the Phrygian Naassenes); and

3) Systems that had a common Jewish background and were close enough to be felt as competing with or distorting the Church’s message (such as the school of Simon Magus).

Modern research has broadened the traditional range of what is considered “gnostic” by bringing light to the existence of pre-Christian Jewish Gnosticism, Hellenistic Gnosticism, and Mandaean sources (the Mandaeans are the most striking example of Eastern Gnosticism outside Hellenism).

Primary Sources

The primary sources of Gnosticism are Greek, Coptic, Aramaic, Persian, Turkish and Chinese. There are also the sacred books of the Mandaeans, a sect which survives in modern Iraq, and includes John the Baptist among its prophets. This is the only instance of the continued existence of a gnostic religion to the present day. “Manda” means knowledge, so Mandaeans means “Gnostics”. There are also Coptic-gnostic writings, mostly Valentinian. Coptic is the Egyptian vernacular language of the later Hellenistic period, descended from ancient Egyptian with a mixture of Greek. The promotion of Coptic as a popular language reflects the rise of a mass religion. In 1945 the miraculous Nag-Hammadi discovery in upper Egypt brought the Gospel of Truth of the Valentinians. Until then the Coptic-gnostic writings like the Pistis Sophia represented a declining stage of gnostic thought. Other primary gnostic sources are Manichaean Turfan fragments in Persian and Turkish; the Corpus Hermeticum first published in the 16th century (it was called Hermetic because of the syncretistic identification of the Egyptian god Thoth with the Greek god Hermes); Alchemicistic literature; Greek and Coptic magical papyri; and New Testament apocrypha.

Secondary Sources

Secondary sources about Gnostic thought are the anti-gnostic works of the Fathers Irenaeus, Hippolytus, Origen, and Epiphanius in Greek, Tertullian in Latin. Clement of Alexandria left writings of Theodotus, a member of the Valentinian school of Gnosticism. There are also refutations of Manichaeism. The mystery-religions of late antiquity (Mysteries of Isis, Mithras, and Attis) are gnostic insofar as they allegorized their ritual and their original cult-myths in a spirit similar to the gnostic one. Some Rabbinical literature and Islamic literature are also sources.

Adapted from: Jonas, H. (1963). The gnostic religion: The message of the alien God and the beginnings of Christianity. Boston: Beacon Press.